Imagine arriving home in a high-rise tower in Dhaka. You step into the elevator, send yourself up 20 floors, and mentally sigh with relief after a long day. But then you think: “What if a fire breaks out? How safe am I really?” In a city rising sky-high but often pushing short on safety, that question holds real weight. In this article, we’ll explore fire safety in Dhaka’s high-rise buildings: what makes them vulnerable, where the gaps are, and — importantly — how those risks can be effectively addressed.

You’ll learn about why fire safety matters more than ever in Dhaka’s vertical-growth environment, what the major challenges are (from design flaws to regulatory shortfalls), how existing buildings and new ones differ, and what practical solutions building owners, residents and authorities can pursue. Let’s climb into it.

Why fire safety in high-rise buildings is a growing concern in Dhaka

Dhaka’s skyline has changed dramatically in the last decade — apartments and commercial towers keep reaching ever higher. That vertical growth brings many benefits, but it also amplifies fire safety risks. A recent study found that between 2020 and 2023 there were 548 fires in high-rise buildings in Dhaka, resulting in injuries and fatalities. (concordrealestatebd.com)

High-rises are inherently more complex when it comes to fire safety: tall heights, multiple occupants, mixed uses (residential plus commercial), longer evacuation routes, smoke and heat moving faster upward — all increase the challenge. The research on Dhaka’s high-rise buildings notes design flaws, deficient maintenance, and lack of emergency planning as recurrent problems. (Bangla Jol)

So when you live or work in a tall building in Dhaka, you’re facing different safety dynamics than in a single-storey house. This section sets the stage by showing you why this isn’t just “another building” issue — it’s a critical safety concern for many people.

Common fire hazards in Dhaka’s high-rise buildings

Understanding what triggers fires in high-rises helps us fix them. In Dhaka, several recurring issues show up. First, electrical malfunctions — overloaded wiring, cheap materials, outdated panels — show up again and again. One study flagged electrical problems as a key cause of fire incidents in high-rise structures. (Bangla Jol)

Second, combustible materials and poor compartmentation: many buildings don’t use proper fire-resistant materials or haven’t designed fire separations (walls, doors) as needed, so once a fire starts it spreads fast. (Academia)

Third, emergency preparedness falls short. Some high-rises lack reliable fire‐alarm systems, sprinkler systems, clear evacuation routes, or even training for occupants. A survey pointed out that while people recognised fire safety was important, many buildings lacked proper plans. (Mendeley Data)

So, behind the appealing façade of tall towers lies a tangle of risk-factors: when the hazards multiply, the consequences escalate. Which leads us to the next section: why high-rises are especially vulnerable.

Why high-rise buildings amplify fire safety risks

High-rise buildings bring a unique set of challenges compared to low‐rise structures. For one, evacuation becomes slower and more difficult — stairwells may become smoke‐filled, lifts cannot be used during fire, and reaching upper floors takes time. Firefighters also face difficulty: equipment designed for six‐storey buildings may struggle when the 20th floor is involved.

In Dhaka, building design issues add further weight: a study assessing “Fire Safety Rating” of commercial towers found that none of the 30 surveyed buildings achieved an “excellent” score in categories like escape facility and built in fire fighting systems. (Academia)

Height means smoke and heat accumulate; if a refuge floor or safe zone isn’t properly designed, occupants become trapped. Long vertical shafts can act like chimneys for fire. Add mixed uses (shops, offices, residences) and you have varied fire loads and occupant profiles. These upward complexities make fire safety in tall buildings much more than just “install a fire-extinguisher and be done”.

Regulatory framework and the gaps in Dhaka

In Bangladesh, several regulations apply to fire safety: the Fire Prevention and Extinguishing Act, 2003, the Bangladesh National Building Code (BNBC) (2000 version and later amendments) set clauses for tall buildings. (Bangla Jol)

Yet enforcement is weak. For example, an official inspection found around 2,603 buildings in the capital declared “at risk” for fire hazards. Many building owners fail to apply for required fire safety licences or renew them. (Prothomalo)

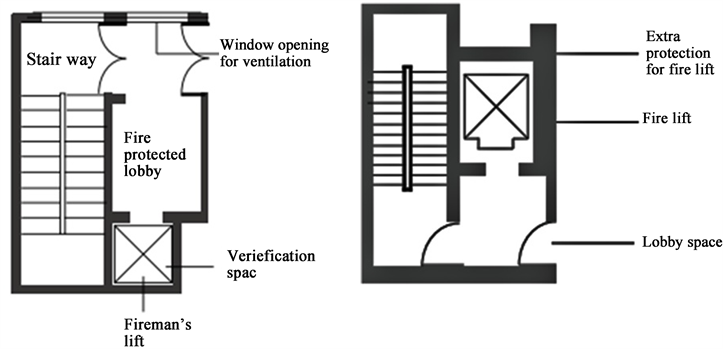

There are further issues around design approvals: one high‐rise (Doreen Tower in Dhaka) reportedly lacked required fire‐protected staircases and firefighting lifts despite its height. (Wikipedia)

Regulation on paper meets reality only partially. The framework exists, but implementation, monitoring, and follow‐through often fall short. For residents and building managers, that gap between regulation and reality is where risk hides.

Practical solutions for fire safety in high-rise buildings in Dhaka

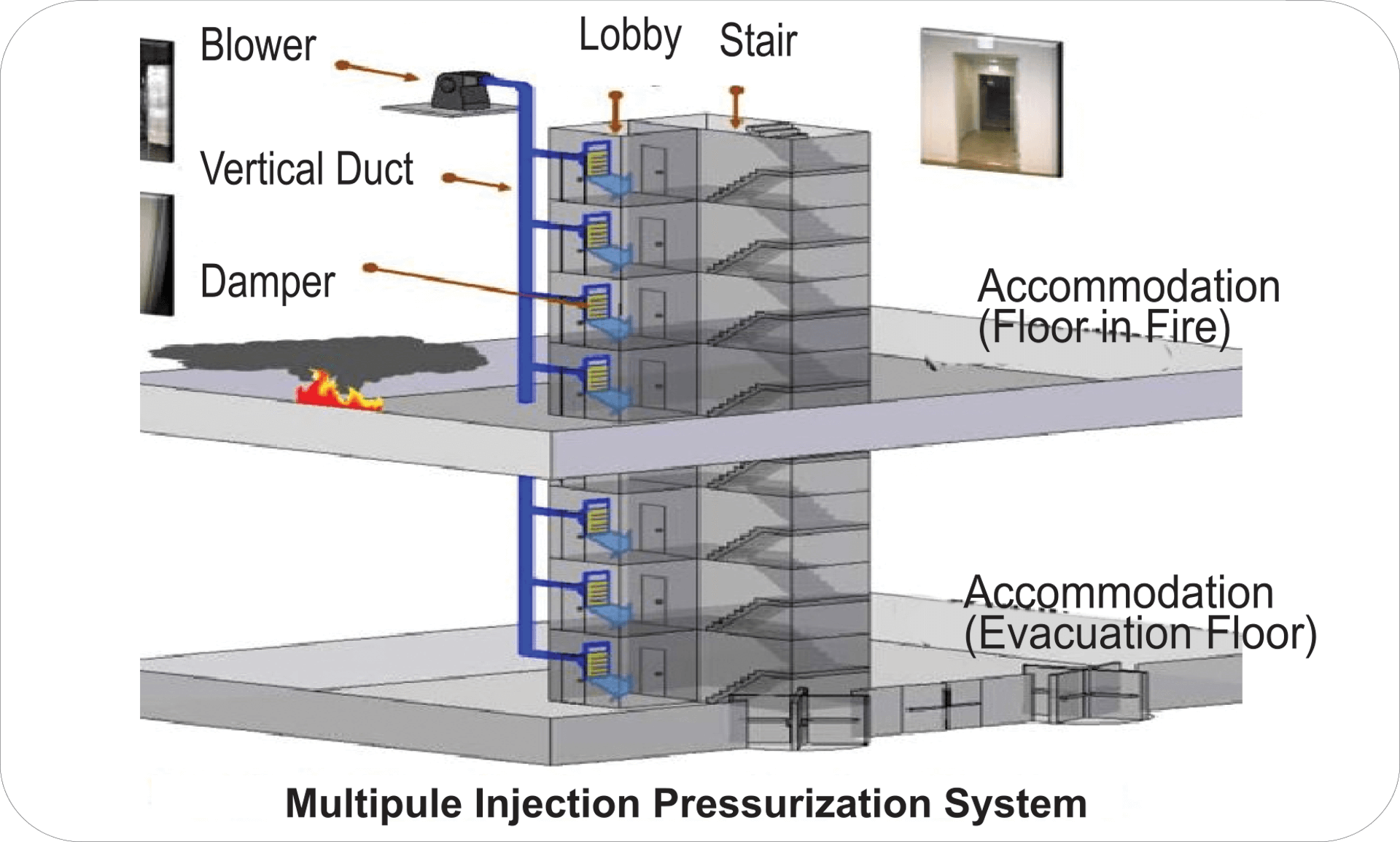

The good news is: solutions exist, and many are practical. First, building owners should invest in active fire protection systems: automatic sprinklers, fire alarm systems, smoke detectors, pressurised stairwells, hydrant systems. A local commentary emphasises the use of fire‐resistant materials, regular inspections and emergency exit planning. (Assure Group)

Second, emergency preparedness matters. Conducting regular fire drills, training occupants, clearly marking exits and stairwells, and having a well‐documented and practiced evacuation plan can make the difference between safe escape and tragedy.

Third, regulatory compliance must be taken seriously. That means ensuring fire licence renewals, implementing the design’s fire protection system, and carrying out periodic maintenance. A recent study on Dhaka high-rise buildings shows that compliance with code is at around 69 % on average—highlighting there’s significant room for improvement. (ResearchGate)

Fourth, retrofit and upgrade older towers. If a building was constructed before stricter safety norms, consider installing modern systems or reworking escape routes. Management committees should push for these improvements.

Lastly, residents themselves play a role. Knowing where the nearest exit is, keeping corridors clear, reporting hazards (overloaded sockets, blocked exits), and cooperating with building management reinforce the entire system.

The human side: resident behavior, awareness and culture

Fire safety is not just about sprinklers and design – it’s about people. In many Dhaka high-rises, occupant awareness remains low. A survey found that many people in commercial high-rise buildings lacked knowledge about fire hazards and how to respond. (Mendeley Data)

Imagine a family in a 15-storey apartment: they know there’s a fire escape, but they’ve never taken the stairs, they keep their corridor cluttered, and they assume lifts work in an emergency. When the alarm goes off, panic sets in, smoke fills the stairwell, and confusion reigns.

Encouraging a culture of safety helps. Management can organise annual drills, distribute clear evacuation maps, keep fire equipment clearly visible and maintained, and hold informal discussion sessions so residents ask questions and feel involved. When fire safety becomes part of everyday talk rather than a hidden checklist, the whole building becomes more resilient.

Real-world example: tragedy turned into lesson

A hard example: in 2019 the fire at FR Tower in the Banani area of Dhaka killed at least 26 people. One key problem: smoke-filled stairwells and blocked exits made evacuation extremely difficult. (concordrealestatebd.com)

More recently, in March 2024, the fire service declared more than 2,600 buildings in Dhaka as “at risk” for fire hazards. (Prothomalo)

These incidents serve as sharp reminders: when a high-rise isn’t designed or maintained for fire emergencies, the consequences can be devastating. But they also provide lessons — better design, clearer escape routes, more vigilant maintenance and resident awareness can change the outcome.

How new construction high-rises can avoid past mistakes

For newly built high-rise towers in Dhaka, the opportunity is ripe to build fire safety in from the start. That means good architectural design with protected stairwells, safe refuge floors, proper firefighting lifts, and clear separation of hazard zones. A study noted that for buildings above 33 metres, a fire protection plan is required in high-rise buildings under building code drafts. (SCIRP)

Further, design teams should incorporate fire‐resistant façade materials, compartmentation to slow fire spread, and ensure that critical systems such as sprinklers, smoke exhaust and alarms are installed. Ownership/management must commit to annual maintenance, system testing, and drills.

Developers should also engage fire service during design approval, obtain fire-license early, and verify that the building infrastructure (water pressure, hydrants, emergency power) is truly equipped. Governments and building regulators can support by auditing, awarding certification for “fire-safe” buildings and promoting transparency so buyers and tenants know safety status.

What building managers, tenants and authorities each can focus on

When it comes to fire safety in high-rises, there’s no single actor. Everyone has a role.

Building managers should prioritise regular checks: ensure fire‐doors close properly, stairwells are clear, detectors and alarms are working, hydrants are maintained, and the evacuation plan is up to date. Tenants should keep corridors clear, avoid overloading sockets, know where exits are, and attend drills.

Authorities must step up inspections, enforce licence renewals, penalise non-compliance, and ensure new construction follows the code rigorously. With Dhaka’s density and high-rise growth, governance is key: one study flagged that Dhaka has the highest fire-risk zones in urban Bangladesh, partly because enforcement and infrastructure lag. (SCIRP)

Collaboration matters. If building management, residents and regulators align around safety, the outcome is far stronger.

The future: what fire safety in Dhaka’s high-rises could look like

Looking ahead, fire safety in Dhaka’s high‐rise buildings can evolve. Smart systems could detect fire earlier and automatically alert fire services. Real‐time monitoring of sprinklers and escape routes might become standard. Greater data on building safety ratings could be publicly available, enabling tenants to choose safer buildings.

Architectural trends may emphasise refuge floors and naturally ventilated safe zones (studies show that natural ventilation on a refuge floor can improve survival conditions). (arXiv)

From a policy perspective, stronger enforcement and regular audits (every few years) may become mandatory. One study in Bangladesh found that code compliance in many buildings was under 70 percent. (ResearchGate)

Ultimately, the goal is clear: Dhaka’s vertical future should not be an unsafe future. With the right mix of technology, regulation, building practice and occupant culture, high-rises can be safe as well as tall.

Conclusion

In Dhaka’s sky-reaching ambition, fire safety cannot be an afterthought. We’ve seen how high-rise buildings present special vulnerabilities — long evacuation paths, complex design, high occupant loads — and how Dhaka’s regulatory, structural and cultural systems often lag. But we’ve also seen that practical, implementable solutions exist: from sprinklers and fire drills to regulatory compliance and resident training.

Whether you’re a tenant on the 18th floor, a building manager, or a developer planning a 30-storey tower, the message is the same: fire safety matters now, not later. Encourage your building to audit its systems, participate in drills, ensure exits are clear, and make fire-safety a regular conversation. Tall buildings should bring height, not hazard.

If you’d like help assessing fire-safety standards for a specific building in Dhaka, or want to know what questions to ask when you move into a high-rise — let me know. Safety starts with awareness, and awareness leads to action.